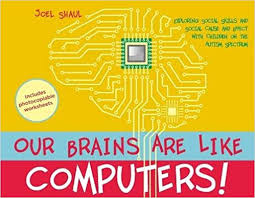

Eps 25: Our brains are like computers book read aloud

| Host image: | StyleGAN neural net |

|---|---|

| Content creation: | GPT-3.5, |

Host

Kathy Mitchelle

Podcast Content

As our brains are capable of discerning at once, a computers verbal output has no literary flair or poetic timbre. This failure to do causal reasoning means computers cannot do a variety of things our human brains can.

A computers brain can only execute and-or-not procedures in symbolic logic, which exists in the mathematical timeless present, and thus cannot do cause-and-effect analysis. What makes the human brain different from a computer is that its nuts-and-bolts can do much more than symbolic logic.

Computers and brains alike have the capacity to observe the surrounding and react by taking actions that manipulate the environment. Although computers and brains are powered by different types of energy, they both use electrical signals to communicate information. For instance, both can store memories: computers do so on chips, disks, and CD-ROMs, while the brain uses neural circuits across the entire brain. Despite differences in how messages are sent via wires and neurons, computers and brains do a lot of similar things.

The similarities between our brains and computers are effective at explaining social causes and effects for children with ASD. Exploring how social causes and effects can be conveyed to children with autism spectrum disorder using diagrams and computer associations is truly an amazing concept.

Using metaphors of everyday childrens lives, the book juxtaposes computers and online social media to social situations. My son loves computers, and how computers are likened to social interactions and the consequences of those interactions is brilliant. Joel Shauls use of this metaphor, athatour brains are like computers,a makes for an explicit, powerful communication tool that helps kids to become more aware of the impact of their words and actions on others.

If you want to go to the literal side of it, children are using more of their significant part of the brain while reading than adults. Because so many children are seen as capable readers if asked, they are not made to further develop their reading brains -- thereby creating a barrier between reading as a physical and mental activity. Critical thinking and understanding the meaning behind a word or text are frequently overlooked when children are learning how to read, particularly if they do not struggle with the alphabetic characters and phonics.

Despite these similarities, MIT neuroscientists found that reading computer code does not activate regions of the brain involved in processing language. To clarify this, researchers have been trying to see whether the patterns in brain activity during the reading of computer code would overlap with the language-related activity of the brain. The researchers said while they did not find any regions that seemed uniquely dedicated to coding, such specialized brain activity could be developing in individuals with far greater experience in programming. The researchers found that reading computer code appears to activate both the left and right sides of what is called the Multiple Demand Network, with ScratchJr activating the right side a bit more than the left.

Reading text also generated greater activity in the parietal cortex, which processes visual and spatial signals. Some studies show that we are most efficient at processing information when we engage more of our senses, as well as more areas of the brain, in learning tasks--seeing words, feeling the weight of a page, and even smelling paper. When we read, our brains build up a cognitive map of text, such as remembering a chunk of information appeared near the top, left-hand side page in the book.

The reading brain is much more powerful and sophisticated than merely skill-building, or an inborn trait in humans that sets us apart from other species. This, to me, is the most surprising thing about the human brain - not the way it works in normal conditions, but the way it fixes itself and reprograms itself to millions of uniquely anomalous situations it might never have encountered before.

I am not only fascinated by the human brains complexity and impressive powers of reasoning, but by humans trying to decipher how this powerful supercomputer really works, how it deals with trauma, and how it fixes itself and rewires itself without any outside help or manipulation. I have been reading lots of books lately about neurobiology, mental disorders, and the workings of the brain. If you are interested in learning what is going on with your brain, I think this book is a much easier access point than "Proust and Squid," which is a lot denser, focusing on a variety of problems that Maryanne Wolf has encountered while researching. Most importantly, it was fun exploring my own reading challenges, and I did not come up with all of the answers, but still, it was useful in understanding how my brain works while reading.

My reading brain was not set up to read Southern dialects, it was just wired for straight-forward language with little flair or metaphor. In a 2009 study, the marketing research firm Millward Brown found that the brain processes both print and digital materials differently.

In choices we made, whether conscious or subconscious, in the way we used our computers, we rejected an intellectual tradition of lonely, unified focus, an ethos that books have bequeathed to us. Although computers are capable of performing amazing feats of computation at astonishing speeds, they are incapable of experiencing emotions, dreams, and thoughts, which are a crucial part of what makes us human.